Genealogy of Models

A 'genealogical' description of traits (memes) and allied notions that have arisen in the historical development of ML models. Memes may only be extracted from papers which contain specific models, rather than being conceived of in the abstract. The practical utility of this study is to extract a library of empirically-proven schemata from which to build new networks. Many links may be dead! This is because I have tagged things here in advance of having actually written the corresponding pages. Motivation / methodology / etc below.

Model Genealogy

Recent models

-

Resnet VAE

Variation of pixelcnn which has two stacks of convolutions with gated activations for maximal receptive field size

-

Pixelcnn++

Very strong early convnet that was the backbone for the first diffusion nets

convolution relu small-kernels transposed-convolution unet-skips ushape dropout elu logmix trainability

-

Gated PixelCNN

Variation of pixelcnn which has two stacks of convolutions with gated activations for maximal receptive field size

autoregression convolution residual relu softmax-multinomial gated receptive-field

-

Pixel Recurrent Neural Networks

Autoregressive model which is an important immediate ancestor to many important convnets

idiotropy autoregression multiscale convolution residual relu softmax-multinomial gated receptive-field

-

Resnet

Primary progenitor in the use of residual layers

residual vgg-rule convolution relu weight-decay small-kernels bottleneck trainability architecture

-

Unet

Core image2image architecture and inspiration for backbone net in early diffusion models

convolution relu small-kernels transposed-convolution unet-skips ushape dropout depth inductive-bias

-

VGGnet

Important architectural predecessor to modern deep convnets

vgg-rule convolution relu weight-decay small-kernels softmax-multinomial depth architecture

-

FCnet

Fully convolutional network which introduced tconvs for upsampling a la unets

convolution small-kernels ushape unet-skips relu transposed-convolution weight-decay

-

Alexnet

Primary early deep convolutional neural net for use in images

convolution relu local-response-normalization dropout weight-decay softmax-multinomial compute-resources

On the Categories

About the 'Memealogy'

So what is this project about? Or what even is it? It's essentially supposed to be something like a family tree or chronological progression of models I personally have studied or found important. The initial object of study must always be a specific model, and never simply a type of model or a hypothetical model. In addition, there is a bias towards recency. I am interested in pursuing the lineages of our modern day Siegfrieds, so for the most part older papers (e.g. pre 2015) will be present only when justified by strong relation to memes expressed in a modern model.

I suppose that brings us to the second important topic: 'memes.' Excusing the use of such an overloaded term, I think that the idea of a meme is perfectly suited to the kind of study I would like to engage in on this site. Namely, I want to abstract from specific and particular models their relevant characteristics and motifs, so as to chart out a sort of genealogy not just in the sense of a family tree, but also in the sense of tracking expressed and relevant memes about the models we study. It is my belief that when theory and practice are not in communion, an approach which soberly decomposes the expressed and actual traits of practical implementations suggests a theory all of its own. In that sense, you could think of the project as a Baconian-empiricist inversion on the usual 'pedagogical' structure of studying concepts and then finding their implementations in the wild.

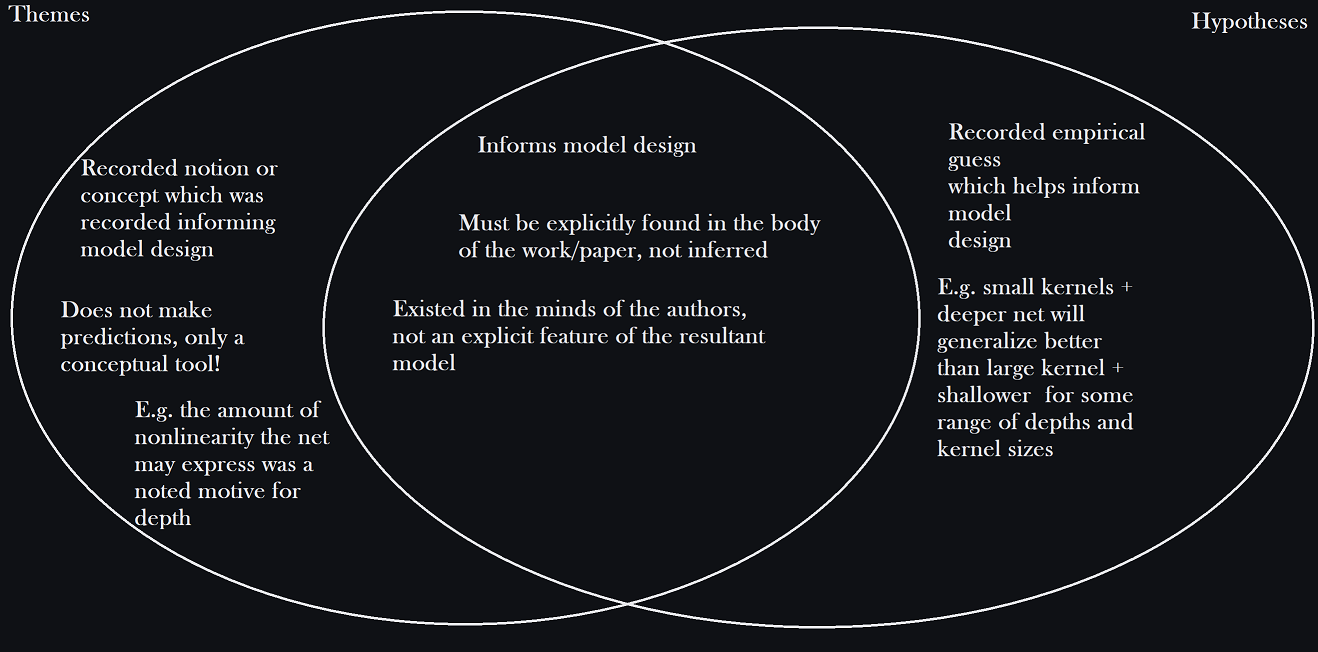

There are a few other categories at play as well. Namely themes, which are characteristics and motifs in the development (verb!) of models, and concepts, which are categories under which individual memes are subsumed for further reflection. Perhaps it is all a little in bad taste. To whoever is interested, this was originally supposed to be a blog post, but I decided to expand the scope. The original introduction of the blog is preserved below as it speaks quite a bit on the purpose of the site itself.

Old Introduction

This is *not* designed to be a beginning introduction of elementary machine learning concepts like loss functions, SGD, autograd, linear fitting, whatever else. It is designed to be a review of architectural changes in networks over time from the perspective of reviewing important papers. I'm going to assume for example some familiarity with ideas like RNNs, CNNs, transformers, etc. Also, it is explicitly focused on neural nets, not general learning methods. I'm really interested in answering the question: what the hell happened? In other words, how did we get the (by my estimation, quite impressive and unexpected) networks we do today? This document is really about doing two things. The first is providing my own waffling, urbane, insipid commentary on a series of papers, which is probably not very useful. The second is organizing a series of papers I think are genuinely worth reading (even if they're relics) in an order which I think does them some narrative justice.

I'll fill this in later. I plan on doing this basically one relevant paper at a time. For now it's just sitting around here as a placeholder. The first paper will cover the RNN -> CNN transition in e.g. PixelRNN -> Wavenet, what I think you can learn from that transition, etc, and a similar situation with transformers. In short, in my opinion after reading a metric ton of papers over the summer (since I decided on a career change into starting an ML business coming from mathematics), probably the most important number would be something like training data processed and applied to weights per compute unit asymptotically assuming taining data / compute is roughly constant as we $\rightarrow \infty$. That's not a very interesting quantitative law, but it's moreso an exclusionary principle. Abstract or theoretical cleverness rarely wins in the face of more data being applied more faster to networks. Sure, we can talk about theoretical foundations for different layer types, but at the end of the day it seems to me that the recent lessons we've seen are that the most important thing is getting a lot of data through the computer subject to the constraint that the transformation can acquire the right topological properties (e.g. arbitrary any-to-any information rather than local processing, relatively-local processing for CNNs, and so on). I don't want to waffle on too long about my personal, subjective ideas. It's not very important. It It seems obvious to me upon reading that the things taught in e.g. college ML courses are usually items of dubious value involving models that are easy to theoretically analyze (e.g. classic VC dimension analysis). I think part of that is basically due to a sort of taxonomic or conceptual misalignment where ML really could be called a lot of different things. You can think of many ML problems as "inference" problems, sure. The training of the practitioners makes that compelling. You could also think of it as function-fitting, similar to classical variational approaches like the Galerkin method, and in that way, you can take more of a classical numerical analysts perspective regarding the whole thing. I personally of course am inclined to that perspective, but it's not very important. The point is that the field is too nascent to even really have fundamental principles we can be absolutely certain are fundamental for-good. Considering how common overfitting has become as a successful strategy, I find it hard to even call the 'bias-variance tradeoff' anything other than canonized ignorance in the sense that it basically is just a problem statement: how do we make our models more able to fit the data when we don't understand much about it, without fitting the wrong latent distributions? The ambiguity in how to extend capacity while ensuring we actually land somewhere we want to with regards to the latent distributions we are trying to model is a 'principle' or 'tradeoff' until it gets solved, and then it's a footnote or starting point for a successful theory. It's very distinct from e.g. the uncertainty principle in signal processing. Obviously 'bad' overfitting is possible, that's not really the point I am getting at. My point is moreso that the field is no longer in a place where the important lenses consist of e.g. balancing variance versus bias, rather than balancing complexity versus compute. There are a lot of situations where you can abstractly show if the data was generated in such-and-such completely unrealistic way that a family of analytically tractable models face some kind of bias-variance tradeoff, but it's not really useful for practitioners or people doing machine learning. It's not necessarily even relevant, because the data we get comes from an unknown but potentially highly rigid (in some way we don't understand) way. Stochasticity is sometimes subjective and sometimes it's not. So the kind of topics we find teachable are very often not topics worth teaching when it comes to this nascent field, and the way we draw the lines as to what constitutes machine learning versus what constitutes this or that, it's pretty wishy-washy and anyone who tells you they know 'exactly' what the field is about is just lying to you. So what's the way to get an idea of what the field is really like or about? My personal conclusion was just to read a lot of papers. Where did the big changes happen, in what papers, and what were the stated justifications? How did later works see those innovations and did the justifications change? Usually, a little bit.

As a side note, I've seen it said that e.g. "well we still teach

The idea in my opinion that there exists a single coherent field we could call 'machine-learning' seems, to me, like it may come to be seen as an idiosyncrasy of our time. That we put topics like nonparametric models next to ideas like the transformer on the basis that both may be applied (only hypothetically) to similar problems seems to be a very loose criterion for determining something as a body of knowledge or field of study. A driving theme in this note is the conviction that there are many different (in 'platonic' terms) subjects which are called machine learning, and that we would like to enunciate a single one as worthwhile for study. I reject entirely that chronology determines the conceptual structure of knowledge (that is, since A precedes B and those who invented B worked within the framework of A for a time, that A is conceptually integral to B; the quaternion example is a perfect one of many in my opinion [2]), and I am doubtful on evidentiary grounds to see e.g. the elegant statistical learning theory of support vector machines as a 'memetically' (rather than temporally, culturally) strong ancestor to e.g. CycleGAN. Of course, there is a common physiognomy to learning algorithms in e.g. the structure of losses, parameter fitting, but that does not preclude the possibility of what I have suggested. Everyone recognizes this to a certain extent, since when one assumes a model with parameters and then fits this model to data, most are rarely inclined to call it a learning method, rather than simply being a matter of 'fitting' (e.g. fitting an AR process, or fitting a linear systems of ODE to some data, et cetera). I think people are the wiser for doing so, but I also think they are the wiser for being skeptical of considering the field we have before us today as an organic and actual whole. The downstream is conclusion that to me, the appopriate method of presentation for these notes is something closer to a 'genealogy' or 'memealogy' of what we have produced of value: models. I do not think the great advances of our time can be measured in terms of conceptual elaborations or breakthroughs rather than in terms of specific models, each often containing combinations of insights rather than singular notions, and which grow out from prior models less in terms of elegant theoretical elaboration than in terms of stochastic mutation and fitness-culling. So the three primary objects of investigation will be *models*, *memes* (recurring motifs and characteristics *of models*), and *themes* (recurring motifs and characteristics *about memes and models*; in other words, something of a catchall for my sloppy taxonomy). In general I will note memes as I found them relevant.

Appendix

Since my youth, I have been inclined to rationalism in the classical sense of the disagreement between the Anglo empiricsts a la Francis Bacon and the e.g. Cartesian or Leibnizian rationalist. Being a German idealist, I would suppose that I still am. The beginning of all knowledge to me must find itself in the mind of the intelligent, rational subject. That being said, in my maturity I have been forced to recognize the great practical wisdom of Francis Bacon. I leave you with a quote from the Great Instauration:

For after the sciences had been in several perhaps cultivated and handled diligently, there has risen up some man of bold disposition, and famous for methods and short ways which people like, who has in appearance reduced them to an art, while he has in fact only spoiled all that the others had done. And yet this is what posterity likes, because it makes the work short and easy, and saves further inquiry, of which they are weary and impatient... But the universe to the eye of the human understanding is framed like a labyrinth, presenting as it does on every side so many ambiguities of way, such deceitful resemblances of objects and signs, natures so irregular in their lines and so knotted and entangled. And then the way is still to be made by the uncertain light of the sense, sometimes shining out, sometimes clouded over, through the woods of experience and particulars; while those who offer themselves for guides are (as was said) themselves also puzzled, and increase the number of errors and wanderers. In circumstances so difficult neither the natural force of man's judgment nor even any accidental felicity offers any chance of success. No excellence of wit, no repetition of chance experiments, can overcome such difficulties as these. Our steps must be guided by a clue, and the whole way from the very first perception of the senses must be laid out upon a sure plan.

References

[1] Lars Hormander, The Analysis of Linear Partial Differential Operators I, Second Edition, pp. 100-101

[2] https://fexpr.blogspot.com/2014/03/the-great-vectors-versus-quaternions.html

[3] Simon L. Altmann, Hamilton, Rodrigues, and the Quaternion Scandal, 1989 https://worrydream.com/refs/Altmann_1989_-_Hamilton,_Rodrigues,_and_the_Quaternion_Scandal.pdf

[4] A.B. Basset, A Treatise On Hydrodynamics, With Numerous Examples, 1888, Volume 2, p. 1

[5] Tai-Peng Tsai, Lectures on Navier-Stokes Equations, 2017

[6] van den Oord et al, Pixel Recurrent Neural Networks, 2016, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1601.06759