transposed-convolution

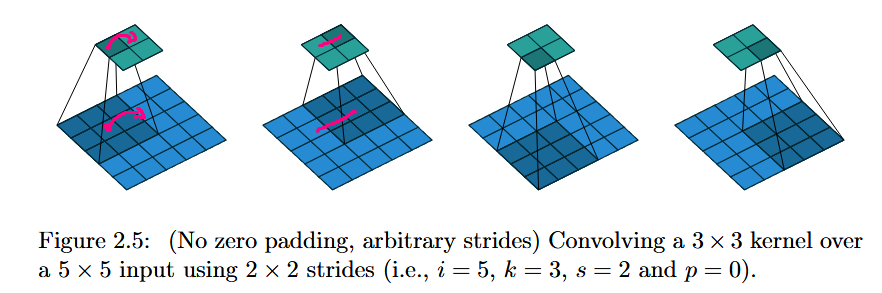

A transposed convolution is in linear algebraic terms the transpose of a strided convolution as a linear map. One less 'formal' way to think of a transposed convolution is that instead of laying a kernel onto the tensor/image and taking the inner product (the sum of products formed with the kernel value at each point with the tensor's value at that point), you multiply the kernel in a transposed convolution by the value of the tensor at a point, and then lay the kernel out onto the area around that point in the tensor. The complexity enters the picture when strides are introduced, but it is also, really, the main point of a transposed convolution. A normal convolution with stride $2$ cuts the shape of its input in half (with proper padding). A transposed convolution has to do the opposite. When you go from one point to the next in a transposed convolution with stride $2$, the kernel is no longer laying over the exact same spot as in the original tensor. Now the way it works is like this: suppose we have a flat rectangular grid representing an image. We make a copy of the grid and scale it up by a factor of $2$, but we keep the coordinate axes the same. Then the transposed convolution at each point multiplies the kernel by the value on the original grid there, but places it in the corresponding spot on the stretched grid, effectively adding twice as many new elements by spacing the kernels apart by two units each in the output, hence doubling the length and width of the resulting grid. I have included a picture from "A guide to convolution arithmetic for deep learning," Dumoulin and Visin, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1603.07285. The footnote contains more details albeit in more mathematical language.

The point of all this is to say that the transposed convolutions are used to increase the spatial resolution so we can symmetrically scale back up. This is a very common technique, but Unets helped to popularize this sort of thing (even if fully-convolutional seemingly 'introduced' it to the literature). Another point of view to consider with transposed-convolutions is that of a stride smaller than $1$ in a normal convolution, where the kernel moves less than one unit, producing many more entries in the resulting tensor:

Another way to connect coarse outputs to dense pixels is interpolation. For instance, simple bilinear interpolation computes each output $y_ij$ from the nearest four inputs by a linear map that depends only on the relative positions of the input and output cells. In a sense, upsampling with factor $f$ is convolution with a fractional input stride of $1/f$. So long as $f$ is integral, a natural way to upsample is therefore backwards convolution (sometimes called deconvolution) with an output stride of $f$. Such an operation is trivial to implement, since it simply reverses the forward and backward passes of convolution.

from fully-convolutional, p. 4. I will probably add more regarding Unet later, since it is such a critical network.

The transpose may always be calculated from a matrix representation in the usual way, but it also may be calculated by solving $\langle u, K_s * v \rangle = \langle K_s^T u, v \rangle$ for $K_s^T$, where $K_s$ is a convolution with stride $s$ and where $\langle , \rangle$ is the inner product, which for discrete sequences or finite sequences (regular vectors) is the dot product, and which for functions over a common domain is $\langle f, g \rangle = \int f(x)g(x) \ dx$. Naturally $K_s * v$ is a downsampled tensor (in the most general sense, because it halves the size of the support), and $u$ must be of the same shape. In order for the equality to hold $K_s^T u$ needs to upsample $u$. If $v = \delta(x - x_0)$ then we get:

$$(K_s^T u)(x_0) = \langle u, K_s * \delta(x-x_0) \rangle$$

so that if we can evaluate the term on the right we'll have an expression for the transpose of $u$. Now

$$K_s * \delta(x-x_0) (y) = \int k(sy - x)\delta(x-x_0) \ dx = k(sy - x_0)$$

so we have:

$$(K_s^T u)(x_0) = \langle u(y), k(sy - x_0) \rangle = \int u(y) k(sy - x_0) \ dy. $$

Setting $u = \delta(y-y_0)$ we get:

$$(K_s^T \delta(y-y_0))(x_0) = \langle delta(y-y_0), k(sy - x_0) \rangle = k(sy_0 - x_0), $$

where for tensors the $\delta$ functions are just the standard coordinate functions. Where a normal transpose has the coordinate representation:

$$(K_s \delta(x-x_0))(y_0) = \langle \delta(x-x_0), k(sy_0 - x) \rangle = k(sy_0 - x_0),$$

from which we can see that the only difference is swapping the order of the indices $x_0$ and $y_0$. Let's suppose our functions/tensors are one dimensional and $k$ is $0$ outside of $[-m, m]$. As a function of $y_0$, $k(sy_0 - x_0)$ is $0$ outside of $[-m/s, m/s]$ even at $x_0 = 0$, whereas for $x_0$ it retains its normal character. The columns in the matrix point of view for $K_s^T$ are translates of $k$ run 'backwards:' $C_{ij} = k(sy_i - x_j)$, and as an operator acting on functions that only take on nonzero values in a bounded area like $[-N, N]$, we can assume $C_{ij} = 0$ when $j > N$. When $|i| > 2N/s$, we have $C_{ij} = 0$ for all $j$.